Get Particular: It’s Money, Not a Kidney

This post is the second in a four-part series about effective fundraising strategies for worthy causes like BRAKING AIDS® Ride. Part 1, “Get Personal: It Works” was about the willingness to share yourself with donors about why you ride. Today’s post focuses on how you ask donors for money to support your efforts.

Ask your donors for a specific amount of money. This recommendation tends to cause most people the greatest discomfort.

After 12 years of doing it, I still feel queasy when I sit down to fundraise. And something about requesting concrete donation amounts exacerbates my insecurities about asking to begin with. The what if-ing tailspins of self-doubt take over. What if it’s awkward? What if people reject me or think I’m arrogant? What if they ignore me? What if they don’t have anywhere close to the amount? What if they’ve lost their jobs? What if they’ve been sick? What if I’m annoying them? What if I’m a total asshole for asking anyone for anything, ever? What if. What if. What if.

You already know the answer here. Most of these projections are your own anxieties and will not come to pass. Even if any or all these what-if scenarios happen, none of them are the end of the world. Here are the reasons why asking for a concrete donation amount is important and effective:

- People are inspired by bold goals, not offended by them. In 12 years, no one has ever expressed anger or disappointment over how much I’ve asked of them. To the contrary, the more audacious I’ve been willing to be about how much money I pledge to raise, the more people in my network have stepped up in their generosity—and I didn’t set a $20K goal until 2016. Irrespective of their financial capacities, just about everyone has commented that they’re grateful and flattered to be part of a collective experience that’s big and impactful, regardless of what amount they can actually donate in a given year.

- People rise to the occasion. Most people give more when you ask for a specific gift amount. You’re asking on behalf of an important and worthy cause, not for yourself. Approaching that task with specificity shows people that you’ve crunched numbers and done your homework and that you’re serious about the target amount you have committed to raising overall. Specificity also maximizes every donation you receive. In the absence of a concrete figure, most folks default to a gift that’s far lower than what they can afford: We’ve all gotten requests for undetermined donations and popped off $25, $30, $50, even when we could have managed double or triple those amounts. When those same requests ask us to donate $150 and explain what the amount funds, far more of us will give $150; a few will be inspired and give more than what was requested; and those who don’t give $150 will donate whatever their budget allows that’s closest to that amount. Being specific is how you ensure that someone who can afford a $150 donation gives that much.

- People give to charitable causes what they can afford. Despite that nagging voice in your head telling you otherwise, no one will think ill of you for asking for an ambitious amount of money to end AIDS. You’re not going to bankrupt anyone by requesting a lot. When people don’t have what you asked for, they will give what they can. If they don’t have any money to give at all, be gracious and ask them if they’d be willing to share your fundraising info with others they know.

The “get particular” directive about money leads to related, common stumbling block for fundraisers: How do you know what target amount to ask for? What’s “realistic”? Unless it’s someone whose personal finances you know well, which is rare, the honest answer is, you don’t know. When I ask for a donation amount, I’m making an educated guess about what people can afford, and I might well be wrong. I’m certain I have been wrong. That’s okay. If people can’t give that much, they won’t—end of story. Missing the mark has very little downside beyond your own ego.

My rule of thumb is to divide my donor list into tiers before I contact anyone. I try to imagine a viable stretch goal for each tier, given what I know about the people in my network and their financial resources—a number that may be a reach but that doesn’t feel divorced from the reality of their circumstances. Think of it this way: If the people you’re thinking of can drop $30 or $40 on brunch or spend $100 going out on Friday night without batting an eye, asking them for $150 to end AIDS shouldn’t feel like an affront or out of the question.

If you’re younger and most of your network is also young and/or in lower earnings brackets, the lowest tier amount you ask for might be $50, $75, or perhaps $100. At this point in my life, my lowest big tier is usually $150 (though I know some people with limited resources of whom I’ll ask $100). Those amounts can still be a serious reach or unfeasible for folks who don’t earn much, but even for them, getting that $100 or $150 request is reasonable, not obscene or tonedeaf. For this reason, this tier is also the one I default to if I don’t know much about the economic status of a prospective donor.

The upshot is people respect candor and directness, especially when it’s about money they’re being asked for. You’ll progress to your fundraising goal a lot more quickly if you’re proactive and specific about the levels of support you need from donors to get there.

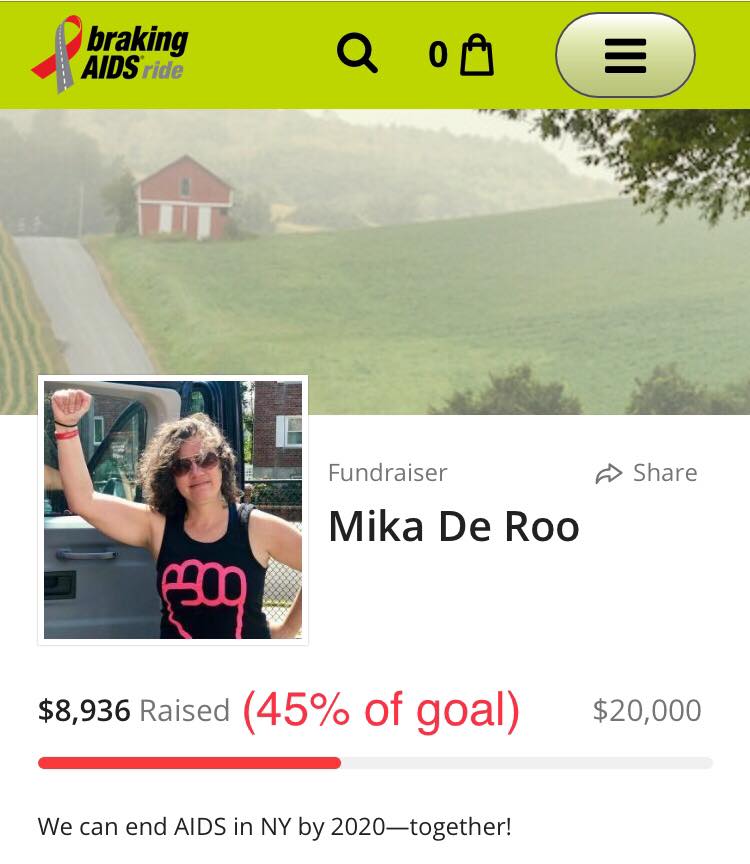

—Mika De Roo, Rider #32